With the responsibility of over 42,000 flights each day, the Federal Aviation Association (FAA) and the North American Aerospace Command (NORAD) have the extraordinarily complex task of maintaining control and order over the United States’ airspace in order to ensure the safety of aircrews, passengers, and people on the ground (FAA). To carry out this mission, the FAA and NORAD use a variety of methods that enable them to track, interact with, and control various aircraft within their jurisdiction. However, due to the recent airspace incursions by unauthorized surveillance balloons and new developments in civilian and military drone technology, many have called into question the ability of the FAA, NORAD, and other government agencies to properly maintain control over US airspace.

At the core of US airspace management is the FAA-organized air traffic control (ATC). With over 14,000 highly trained operators stationed throughout the country, ATC is charged with providing authorization to aircraft from the moment they start their engines at their origin, to the moment they stop them at their destination (FAA). ATC dictates which taxi way an aircraft uses, the runway they take off and land from, and most importantly, the squawk code used to track the flight. Squawk codes are 4 digit numbers that are imputed into the aircraft’s transponder and then are broadcast to many tracking stations on the ground, as well as any aircraft in the surrounding area. Most flights–both general and commercial–will receive a unique squawk code which on an FAA server will be paired with the aircraft for the duration of the flight. Websites such as FlightRadar24 have partial access to these servers which allow them to display the location, altitude, and model of every registered aircraft in the sky at any given time. Certain squawk codes are reserved to convey important information such as 7700 which is reserved for use by a plane undergoing an emergency situation, or 7500 which is used for an aircraft undergoing an attempted hijacking (Spartan). Despite being the most utilized form of airspace management, and legally required for all nonmilitary flights, squawk codes and interaction with ATC is only effective for aircraft that choose to cooperate with it.

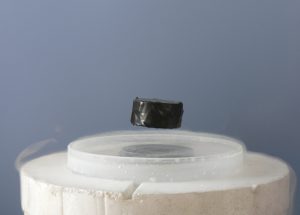

The second layer of US airspace management, primarily used for defense and as a backup to the FAA’s solutions, is NORAD’s vast array of ground based WSR-88D Doppler radar systems. There are 155 publicly known radar installations in the United States and its territories. However, it is likely that many more exist as backups in the case of an attack targeted at these stations (NOAA). In addition to NORAD, these installations are utilized by a number of federal agencies including the National Weather Service; however, their primary purpose is to track objects entering and operating in US airspace. To do this, Doppler radar installations emit radio wave pulses at specific frequencies and wavelengths. These pulses are emitted for 1.57×10-6 seconds followed by a 9.9843×10-4 second listening period for reflected radio waves. The time it takes for these deflections to return to the radar dish dictates the distance of the object from the dish, and changes in the frequency and wavelength of the radio waves help to inform operators of the size and type of object that is being detected (NOAA). Stealth aircraft attempt to evade radar detection by using sharp angular panels to limit the radio waves that are deflected back toward the installation. However, with enough of these installations operating throughout the country, a clear map of most aircraft can be produced regardless of their compliance with ATC and FAA regulations.

Despite being relatively old, these two systems working together have proven to be a very reliable method of maintaining order and safety within US airspace. While concerns over emerging technologies such as civilian drones are valid, the FAA is actively taking steps to improve their monitoring capabilities by requiring transponders similar to those found in aircraft and in drones weighing 250 grams or more thus limiting their operation to a ceiling height of 400 feet (FAA). While the sky over the United States is home to some of the busiest airspace anywhere in the world, it is managed with precision and efficiency and will continue to adapt to the challenges of the future.